- Home

- Lindsey Grant

Sleeps with Dogs Page 9

Sleeps with Dogs Read online

Page 9

Once I reconciled that Charlie was my best and only antidote to loneliness, I tried to buddy up to him. He wasn’t having any of it. Given my inability to pamper him in the manner that Katherine seemed expert at, Charlie largely ignored me and got even more cantankerous as our time together wore on. He ate less but farted more. I imagined him cutting his eyes meanly at me as he left the room in the wake of his outrageous flatulence. He spent most of his time prostrate in the corner of the living room, dangling his head at an unnatural angle out of his bed, his tongue lolling.

Feeling rejected and bored, I attacked the four-month-old stash of Halloween candy in the freezer, tucked in the back behind the rows of dog treats. I carefully rearranged the remaining candy to disguise the large dent I put in it. It was the only thing in the house to eat, except of course for Charlie’s cottage cheese and hardboiled eggs. I’d already eaten as much of the peanut butter in the cabinet as I dared without it being obvious. Of course, I could grocery shop for myself and keep food in her fridge, even cooking my meals in her fully functional kitchen. But, aside from avoiding further ways I could destroy her perfect house, I was also trying to save money from my narrow profit margin to eventually get an actual apartment.

As it was, crashing with my mom’s best friend and her family on those nights that I didn’t have overnights was undeniably convenient and economical. They were very generous to let me use their attic bedroom, and I was more than happy to help them out with domestic errands and the like in repayment. But six months of nomadic overnight nannying interspersed with what amounted to semi-permanent couch surfing had me longing for a room—or two or three—of my own.

When I went to work in the morning to do my usual rounds, Charlie refused to go outside to the garden. Instead, he ran around the house, dodging and barking shrilly when I came close. No amount of wheedling, bribery, petting, or kissing seemed to win Charlie over to my favor, and I suppose I deserved it.

It’s not like he was the first animal I hadn’t seen eye to eye with. Most recently, there’d been Cha Cha, a Chihuahua living in a duplex occupied by her owners—a couple, each living on their own side. Two people in a relationship living next door to one another and sharing the dog between them. That should have been the first flag.

Throughout the entire meeting, convened on Her side of the duplex but attended by Him as well, the tiny dog barked viciously and lunged at me, baring her miniscule but very sharp teeth.

“Oh, she is just protecting us,” they’d both blustered. Cha Cha was little bigger than my foot, and I could’ve easily punted her through the living room window. The intensity of her apparent hatred for me was unnerving. I was trying to assure the clients of my competence but couldn’t help jumping visibly at every bark. Any sudden movement on my part elicited a pointed snapping of her jaws, alarmingly close to my exposed wrists. I took very few notes during that meeting and tried not to move any more than I had to.

I managed to remember, however, that I was to come in through the back door of Her apartment, where I’d find a plate of cut-up hot dog. I would microwave that, tantalize Cha Cha with the treat, and hook her up to her lead for a walk while she was distracted by the hot dog pellet.

Upon my first—and only—visit with this pint-sized killer, I did manage to enter through the back door and microwave the hot dog. I attempted the distract-and-clip maneuver earnestly, offering the hot dog with one hand while aiming to hook the leash to the tiny D-ring at the back of Cha Cha’s neck with the other. But that was met with more barking, bared teeth, and growling. Failing that, I tried tossing the hot dog and then sneaking up behind her with the leash. It all ended when she bit me and then peed all over the floor.

As Katherine’s return approached, I got paranoid that she would psychically know about the candy, the washing machine, and everything else that had gone wrong during my stay. Even at twenty-two, I still lived in fear of “getting in trouble” or being accused of not doing something to perfection. For as long as I could remember, I placed unrealistic expectations upon myself—to be agreeable, amusing, unobjectionable in all ways. In school, an A– was not acceptable to me. The scholarship I received in college wasn’t the best available, and thus I deemed it a failure. This pressure and these judgments came from me alone, and not my parents. They rejoiced over my one B grade, reading it as a sign that I was normal. They celebrated my fallibility, hoping this counterintuitive form of encouraging mediocrity would help me relax.

I recognized in Katherine a similar demand for excellence. Though where I strove, she seemed to succeed. Her standards, in fact, far exceeded mine, for I felt keenly while I was in her home with her dog that I fell obviously and irredeemably short of good enough in everything from having to use a towel to protect her bed linens from my zit cream, to my inability to bond meaningfully with Charlie as she had.

Rationally, I knew that if Katherine fired me, I wouldn’t have my business license revoked or go to jail, and I wouldn’t be heartbroken to never see Charlie again. But it really chafed me that I didn’t nail this assignment. Even if Katherine couldn’t tell—even if she never knew what went on in her house those days that I was there—I knew. I’d done everything expected of me where Charlie was concerned, yet I still had the distinct feeling of failure.

I spent a lot of time worrying about the tiny hairless patch left by the tree sap I’d yanked out, too. I saw a Beavis and Butt-head episode once where they gave themselves beards of head-hair, trimmed and then glued onto their chins. I thought that maybe I could trim some of his haunch fur, where it grew thicker, and glue it to the bald spot.

I wondered if three to four days’ time was enough for Rogaine to take effect on a dog. But then I was afraid it would have some reverse effect on dog fur and make the bald spot bigger. I brushed the area compulsively, trying to arrange the surrounding hairs to mask the little spot, like a canine comb-over. Late into the evening, I stood across the room, and then closer in two-foot increments, trying to determine how close one had to be to notice the missing fur in Charlie’s otherwise-perfect coat. He definitely looked thinner and was sleeping more. Or was he sleeping less and eating more?

Either way, it was clear to me that my isolation from people and near-exclusive interaction with dogs was taking its toll. I’d realized how singular the focus of my life had become at Christmas, during a visit from my parents. They’d occupied the pullout in Annie’s den for the better part of a week, visiting with the family while I traveled hither and thither, my schedule crammed to overflowing due to the high volume of out-of-town clients over the holidays. I was beyond touched that they’d foregone their own deeply entrenched Christmas traditions to be with me. I made a portion of sauerbraten, marinating it for the minimum three days beforehand, so my dad could have his usual yuletide dinner. On Christmas Eve, before I departed for my final pet-sitting visit of the night, we’d upheld the long-standing ritual of reading “The Night Before Christmas.”

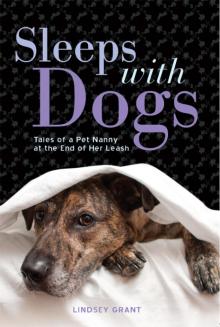

Christmas morning, I stole a few short hours to open presents with them, and every single gift was dog related. I received a pair of “Up on the Woof Top” socks depicting a dog-Santa dropping presents down the chimney; a CD carrying case in the shape of a dog’s head, his mouth the zipper; a matching glow-in-the dark leash for dog and handkerchief for me (safety was a big thing for my parents that year, and always); pajamas from my sister and brother-in-law, sent with my parents, that read “Sleeps with Dogs” across the chest; a dog-themed address book, the dogs themselves illustrated as gumshoes, society molls, thespians, and roughnecks; a plastic purple poop-bag dispenser in the shape of a dog bone; a coffee-table encyclopedia of dog breeds; yet another subscription to Bark Magazine (my third); and a dog-paw-print “From the desk of” notepad, my name misspelled with an a instead of an e. My mom was profusely apologetic about that, claiming the manufacturer misread her personalization.

It was quite a haul. For a brief and surreal moment, I wondered that I hadn’t been given any dog treats or a chew toy, as though I mys

elf had pulled a canine metamorphosis and turned into a dog over the past five months. Other interests and dimensions, and certainly some human companionship, seemed immediately in order, lest I should actually start growing fur and barking.

Between the dogs by day, the occasional pet sleepover, and otherwise living with Annie’s family and helping out with her boys, I wasn’t meeting many people. And by people, I mean like-minded—in age or profession or hobbies or otherwise—individuals that could potentially be my friend. I really wasn’t being picky. A human with whom I could recreationally share a meal, or a laugh. Or, if I was lucky, both.

I had a guest pass to Annie’s tennis club and tried to get to as many yoga classes as I could. I found that the stretching helped ease the back pains I got from pounding miles of pavement during my days. The gentle yoga I liked was almost exclusively attended by women in their sixties, all of whom I grew very fond of, but none of whom seemed to be in the market for a twenty-two-year-old SWF BFF new to the area and craving companionship.

If I was expecting to find likely candidates at the monthly association meeting of area pet-care professionals, I came up empty handed there as well. I was at least ten years younger than the youngest of the other business owners, but proximity of age was less material in my friend quest than overcoming the distant yet professional cordiality that was the norm in the group. We were, ultimately, competitors in a fairly tight market.

I could tell early that there were alliances between business providers—walkers that helped each other out, or greatly respected each other’s integrity. But this wasn’t an environment ripe for grabbing a drink afterward, or making plans for the following weekend. Nor was it the place to gripe about particularly quirky clients, or tell stories on ourselves, admit recent screw-ups, or air our dirty laundry. Everyone was looking for a small edge on the others, and mistakes were remembered, catalogued quietly, and judgmentally held close. An ill-mannered dog that didn’t improve over time could tarnish your reputation; if you took on a client that handled their pet irresponsibly, somehow that irresponsibility transferred to you. Everyone knew who’d been sued, or who would surely get sued any minute now; who ran chronically late; which walkers took more than the maximum number of dogs out on the trails; who charged too much or too little.

So I minded my p’s and q’s, tried not to ask too many questions, always complimented that week’s snack-bringer on their baking or their choice of chips, and assiduously logged the meeting minutes, which I emailed out to the LISTSERV no more than five days following the meeting. I didn’t want to gain a reputation as a procrastinator. Or an incomplete-minutes-keeper. I already felt that my age and relative inexperience were dings against my otherwise acceptable reputation within the group. And, ultimately, I accepted that I was going to need to look further afield for that much-needed human companionship.

I was out with Charlie on our most successful walk yet when my phone rang. Normally I didn’t pick up when I was out with a dog—trying to have a conversation simultaneous to walking distracts me from noticing cars, other dogs, and countless other factors that could become problematic for me or the dog. Having one hand occupied with a phone and the other with the leash makes picking up a hot fresh poop nearly impossible. Charlie had reached the outer limit of his comfort zone at the end of the block and was poking around in a patch of ivy, hopefully getting ready to do his business. We could hang out there for a minute, so I answered.

It was a friend from my undergrad years who was finishing up his master’s in English literature. He’d been sending me his short stories, hugely entertaining fictions about small-town giants, cadavers, hoarders, and misfits. We had taken writing classes together at school, and it seemed like he had more than enough talent and motivation to formally pursue publication.

The sprinklers were on in the neighborhood yards, and the sky was twilight purple. I was trying not to spook Charlie with my telephone conversation and jinx my unbelievably good luck at getting him past the mailbox and down the street, so I was replying to Ian quietly, and in short one-or two-word sentences. I still wasn’t quite sure why he’d called. Usually he just emailed when he had a new story to show me.

While Charlie finally took a squat in the ivy, Ian was filling me in on his recent outbreak of psoriasis from the cold weather and the stresses of school. He said he’d stopped shaving and cutting his hair. He wanted to know what I thought of the last story he sent. I hadn’t read it yet.

“So anyway, I gotta get out of the Northeast. My plan is to move out there at the end of the semester. I think we should live together.”

In a way, we’d lived together before. During our senior year of college, we lived in separate apartments in the same building, a converted train depot that had seen better days. He’d explode into my loft without prior warning, pushing through the heavy ten-foot door, bellowing, “Hello the house!” Sometimes I’d be just out of the shower and standing in the hallway in only a towel. Or once, he came into my bedroom at three in the morning because I wasn’t answering my phone. But I tolerated it. Sure, he had boundary issues, but he meant well.

We ended the conversation with him declaring he’d be out by the end of May, just as soon as he graduated and packed. I didn’t believe he was coming.

In an effort to right all of my supposed wrongs, I brushed Charlie’s teeth. I crept behind the bushes in the garden, scraping up the hard, heavy dog piles. I sat on the floor in the corner, rubbing Charlie’s belly for thirty minutes at a time until my hand felt like corduroy. I ran around the house playing keep-away with him and his teddy. I hoped that my exuberance would dispel any angst or bad juju that was hanging over the house. I fluffed the candy in the freezer, made perfect hospital corners on the guest bed, refolded and returned the beach towel to its place in the back of the linen closet, and gave Charlie his beef-jerky-and-cottage-cheese treat.

I put the key on the dining room table before I left for the last time, along with the invoice and a note in which I baldly lied about how much fun Charlie and I had together.

In the aftermath of those overnights with Charlie, I’d started looking at studios in Berkeley—tiny affairs with kitchens that doubled as the living room and dining room, with walls so close I could almost touch both when standing in the center of the room. One had a slanted ceiling low enough that I had to stoop throughout the entirety of the tour. Still, I didn’t think I could afford anything without having a roommate to share the cost.

I was seriously contemplating a place I’d dubbed “the phone booth”—a two-story converted storage shed with a two-burner stove top, a dorm fridge under the counter, a closet-sized bathroom, and a place beneath the stairs for a smallish chair—when Ian called again.

I’d been so certain he was bluffing, or that he’d flake on moving out to California. Yet there he was on the line, saying, “I can’t think of anyone I’d rather live with, or any place I’d rather be. You can teach me how to cook! We’ll have a book club and exchange our writing for critique. We’ll be writers, and write together in our writers’ den. We can find Michael Chabon and invite him and his wife to dinner!”

“So does May work?” he asked again. “Should I book the ticket?”

I was an easy sell, starved as I was for human contact and companionship in light of my professional sequestration with the animals I cared for. I was, after all, on the verge of renting a shoebox I couldn’t afford, in which I couldn’t even entertain without asking my guest to sit on the toilet lid or my bed. Ian’s enthusiasm was infectious, and I even half-believed we might do one or some of the wholesome, self-actualizing activities he’d described. I said, “Sure.”

The next time Katherine asked me back to watch Charlie for a week, I was staying with a Burnese mountain dog and his three-legged cat companion. The dog was as affectionate as Charlie wasn’t, frequently clambering up into my lap as though he were twenty pounds and not eighty. He was a rapscallion, his puppy naughtiness lingering long past puppyhood. He loved to take

his leash, or the edge of my shirt, in his mouth during walks and galumph off, dragging me in his wake. Worse, he chewed everything he could get his mouth around—napkins, the remote, car keys, socks, and, unfortunately for me, my eyeglasses. I’d returned to his house one night to find some kind of plastic twig dangling from his maw. I pried his jaws open to extract the mystery snack and pulled out the mangled remains of my frames. The lenses had long since popped out, and the rest looked like he’d been grinding on them all day long.

I couldn’t drive, especially not at night, without my glasses, and they had to be replaced immediately. The owners wouldn’t contribute to the cost, either, because I had known in advance that he ate everything, and I’d failed to put my glasses far enough out of reach. Raw deal, and really bad timing, as all of my extra money had been going toward the imminent move.

Whatever I perceived Charlie’s and my differences to be, he wouldn’t have eaten my glasses. When Katherine called, I had a sudden and unexpected rush of gratitude for him and his comparatively dignified, non-meddlesome comportment. I would have taken him on for another week, maybe even making friends with him this time, had I been available. But the dates in question conflicted with the week I was taking to drive from Georgia to California with my mom—a necessary trip, but a major ding to the old bank balance.

Moving out of Annie’s house meant leaving their loaner car behind, a complicating factor of my transition from their attic to my own abode. Annie had of course offered to give it to me for next to nothing, but my parents had leapt at the opportunity to restore my old car to my care. They had no use for the extra set of wheels, and the car itself was a far better fit for this line of work than the Volvo sedan had been. While old, and fitted with manual everything, the car I’d be retrieving was a hatchback with a fold-down backseat, making it ideal for ferrying dogs about as needed.

Sleeps with Dogs

Sleeps with Dogs